Water, energy, environment: smart cities start with good resource management

Ten years ago, the concept of a smart-city still conjured up images of cities built from scratch, using the most advanced techniques and technology available in every field.

Most of us have at least heard of the two most iconic projects of this vision:

- Masdar, a new town in the emirate of Abu Dabi – under construction in the middle of the desert since 2008, this ‘eco-city’ in fact only covers 6.5 hectares (excluding the 22 hectare photovoltaic plant which powers it). Originally, it was meant to accommodate 50,000 habitants by 2030, a total that has since been scaled down (40,000).

- Songdo, a new neighbourhood in the town of Incheon in South Korea – under construction since 2003 over 610 hectares, Songdo welcomed its first inhabitants from 2008, and over time should accommodate a population of 65,000.

We can add to these the project that has transformed the Quayside neighbourhood in Toronto where Alphabet (ex-Google) was intending to relocate the urban innovation of its subsidiary Sidewalk Labs over 324 hectares. The company had to throw in the towel in May 2020 due to economic crisis, but also strong opposition from the inhabitants of Toronto.

At once laboratories and a showcase for technologies, these costly ‘state of the art’ operations were conceived by their promoters as models destined to be reproduced. However exemplary and virtuous they aim to be, they struggle to gain the status of ‘town’ as much from a local point of view (no one moves there to settle due to cost, but not only because of this…) as from our European perspective. In our eyes, they lack substance, both in terms of history and culture and the territorial cohesion that characterise our conception of town and city life. This notion, less to do with technology than our sense of society and heritage, explains why it is so difficult, particularly in France, to demolish in order to rebuild what amounts in some way to a few rows of houses. It also explains why, 60 years after their construction, Marne-la-Vallée, Melun-Sénart and Evry are still seen as ‘new’ towns!

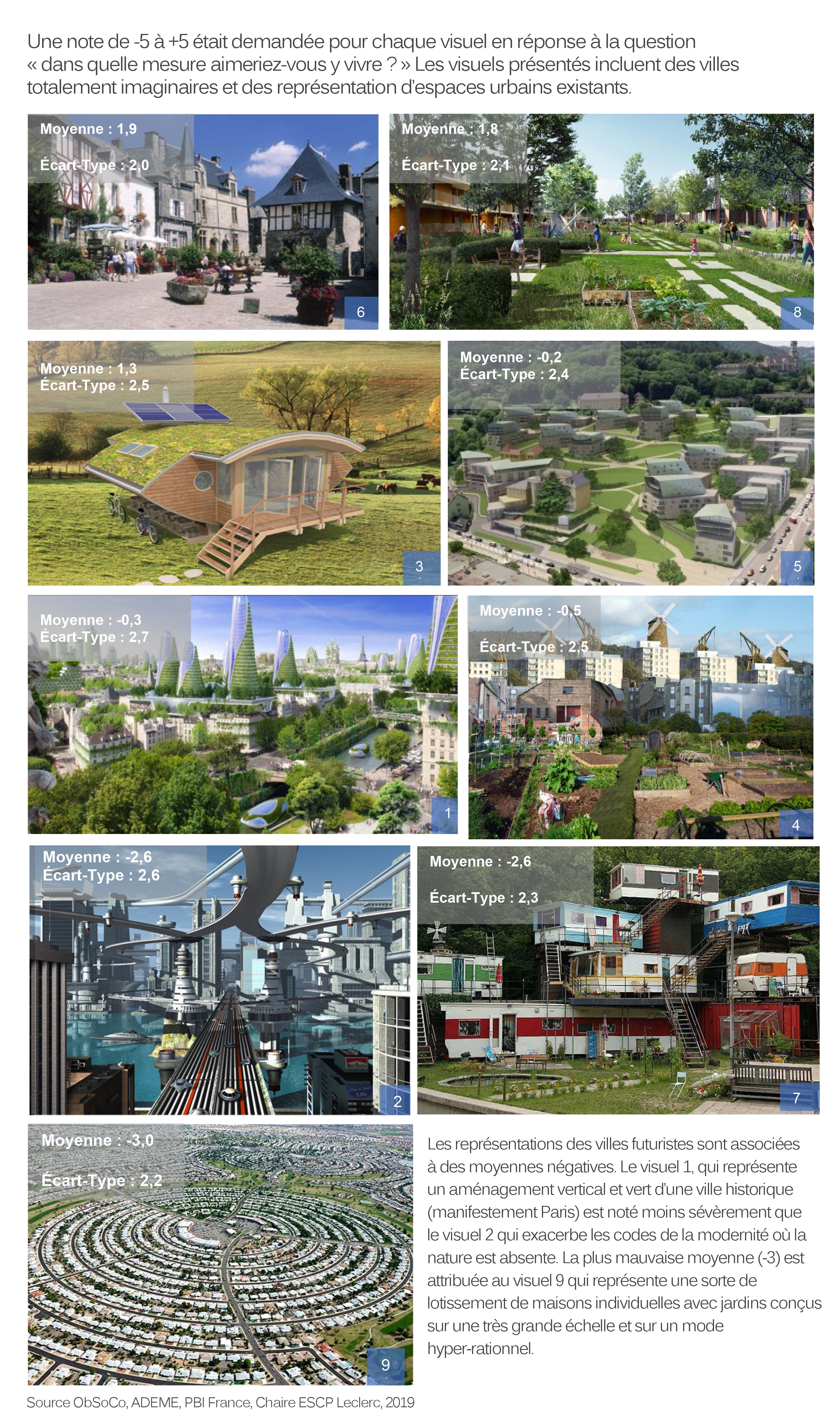

Aware of the challenges to come, the French are nevertheless keen to move forwards. The remarkable study carried out by ObSoCo on “utopic perspectives” (2019) illustrates the viewpoints at work in a 75% urban population. It highlights the rejection of ‘techno-liberal’ and ‘security focused’ visions, which score 15.9% and 29.5% of the votes respectively, and the adherence to the ‘ecological’ vision (54.6% of the votes). The scores given to the different images of towns and cities presented to the participants in this study speak for themselves:

Captions:

- Caption 1: A score of -5 to +5 was required for each image in answer to the question «how much would you like to live here». The images presented included entirely imaginary towns and images of real urban spaces. The average (Moyenne) and Standard Deviation (Ecart-Type) scores are shown on each photo.

- Caption 2: the images of futuristic towns score negative averages. Image 1, which shows vertical and eco-friendly design in a historical city (clearly Paris) is marked less harshly than image 2, which gives prominence to modernist traits and lacks anything from the natural world. The lowest average (-3) was given to image 9 which shows a sort of cluster of individual houses with gardens designed on a very large scale and in a hyper-rational way.

The smart city, «sustainable» first and foremost

Towns of the old continent, rather than starting from a blank canvas, take where they are now as a starting point for their transformation and reinvention as they anticipate the challenges we all know we will be facing in the future. These include energy, climate and environmental issues, but also social and economic ones. Hence, from a European standpoint, the smart city is not so much a “hyper-connnected” town, driven and governed by digital technology. Rather it is a town that has been re-designed to be sustainable on the social, economic and environmental planes. The smart city makes use of the best of technology, but also a certain number of practices that aim to reinforce inclusivity, democratic life and the economic fabric.

This approach emerges clearly in the study published in 2014 by the European parliament. It identifies 240 ‘intelligent cities’ at the heart of the EU by categorising their actions and projects into one or more of the following domains:

- Citizenship – citizen information, access to data and services in the town

- Quality of life – local life, neighbourhood life, social cohesion, ethnic and cultural diversity

- Mobility and transport – traffic management, ‘soft’ modes of transport, car and bicycle sharing, reduction in pollution, management of multi-modality transport and parking

- Economy – start-ups, incubators, co-working spaces, competitive hubs, ICT development

- Environment and energy – positive energy buildings, waste management and recovery, controlled energy and water usage, development of renewable energy, local distribution

- Governance – collaborative/participative democracy, electronic voting, open data

It is not a question of setting one model against the other, where the one vision is of a technical and mechanical city promoted by industrial players through their prototypes, and the other is of an organic and humanist town. The governing concept of the smart city and all the steps taken by self-proclaimed smart cities, is that digital technology will, in one way or another, enable cities to provide more intelligent answers – more ingenious, less onerous, more coordinated – to solve the challenges of urban life over the coming decades.

Creating intelligent networks to preserve resources

Against a backdrop of less urban growth than the emerging and developing countries, cities of the old world (and old cities in general) are all facing the same need for end-to-end control of water and energy resources, as much with the objective of economising on the resources themselves as to save on operating costs for the infrastructures and networks underpinning their distribution. Although these infrastructures have been skilfully constructed, they were built at a time when no one seriously expected that these essential resources might one day be scarce and in danger of running out. In France, for example, water networks are all between 50 and 150 years old.

These aging networks are badly in need of modernization, and all the more so since 20% to 30% of water disappears between the place of production and where it reaches the tap. This means that we’re producing hygienic, quality water at a high price, which is literally being lost in the sand because the pipes are no longer in a good condition, and we don’t know how to locate the leaks and the other weak spots. This water (and energy) wastage obviously pushes up household and business water and sanitation bills. So it is quite understandable that, the world over, local authorities and intermunicipal structures are trying to address the issue of modernising water and sewage works.

Modernisation programmes use the latest technologies available, and in this, NOMADIA is ideally placed to support local actors in their transformation projects. So, for example, NOMADIA partners SUEZ SMART SOLUTIONS: with a 250-strong network of experts throughout the world, this subsidiary of the Suez Group specialises in data collection solutions (smart metres, sensors, probes). Their aim is to feed the digital models and real-time applications communities deploy to develop logical use of resources and resilience in times of crisis.

“NOMADIA’s Opti-Time solution is at the heart of the partnership” explains François Moreau, commercial director at SUEZ SMART SOLUTIONS. “Used by almost 4,000 technicians and planners at Suez, it optimises local interventions, whether during the early phase where the network is being equipped with sensors and smart meters, or in the operational phase to ensure the equipment is maintained. Opti-Time fits perfectly within our client offering, thanks to its capacity to integrate the particular constraints of the water sector in routing calculations. Working together to respond to consultations, we are able to guarantee optimum planning for technical interventions and so less costly management overall.”

SUEZ SMART SOLUTIONS and NOMADIA have now responded collaboratively to various consultations in France and internationally, so we look forward to sharing the outcomes of some interesting projects with you before long!